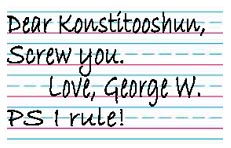

Junior is sneaking about behind Congress’s back and making up his own laws. For example, last week Charlie Savage of the Boston Globe described the signing of the renewed Patriot Act:

Junior is sneaking about behind Congress’s back and making up his own laws. For example, last week Charlie Savage of the Boston Globe described the signing of the renewed Patriot Act:

The bill contained several oversight provisions intended to make sure the FBI did not abuse the special terrorism-related powers to search homes and secretly seize papers. The provisions require Justice Department officials to keep closer track of how often the FBI uses the new powers and in what type of situations. Under the law, the administration would have to provide the information to Congress by certain dates.

So what did Bush do?

Bush signed the bill with fanfare at a White House ceremony March 9, calling it ”a piece of legislation that’s vital to win the war on terror and to protect the American people.” But after the reporters and guests had left, the White House quietly issued a ”signing statement,” an official document in which a president lays out his interpretation of a new law.

Sneaky.

In the statement, Bush said that he did not consider himself bound to tell Congress how the Patriot Act powers were being used and that, despite the law’s requirements, he could withhold the information if he decided that disclosure would ”impair foreign relations, national security, the deliberative process of the executive, or the performance of the executive’s constitutional duties.”

Bush wrote: ”The executive branch shall construe the provisions . . . that call for furnishing information to entities outside the executive branch . . . in a manner consistent with the president’s constitutional authority to supervise the unitary executive branch and to withhold information . . . ”

The statement represented the latest in a string of high-profile instances in which Bush has cited his constitutional authority to bypass a law.

How alarmed should we be about this “unitary executive” stuff? I think the answer is, very.

This FindLaw column of Jan. 9, 2006, by Jennifer Van Bergen provides some good background on signing statements and the unitary executive doctrine. First, let’s look at signing statements:

Presidential signing statements have gotten very little media attention. They are, however, highly important documents that define how the President interprets the laws he signs. Presidents use such statements to protect the prerogative of their office and ensure control over the executive branch functions.

Presidents also — since Reagan — have used such statements to create a kind of alternative legislative history.

The alternative legislative history would, according to Dr. Christopher S. Kelley [PDF], professor of political science at the Miami University at Oxford, Ohio, “contain certain policy or principles that the administration had lost in its negotiations” with Congress.

In other words, Bush can concede a point to Congress, which then writes a law for him to sign, and then after he signs it he writes up the part he had conceded and puts it back into the law.

The development of this particular constitutional end-run is attributed to Daddy Bush by Professor Kelly:

The Bush I administration, for example, worked with fellow Republicans in Congress to create an alternative legislative history on important bills. The alternative legislative history would contain certain policy or principles that the administration had lost in its negotiations with the Democrats. Thus when President Bush signed the bill into law, he would use the signing statement to direct executive branch agencies to the alternative legislative history as guidance of congressional intent.

No wonder Junior hasn’t felt the need to use his veto power. He essentially “vetoes” by rewriting law as he chooses.

Are these signing statements a new thing? Well, yes and no. Ms. Van Bergen says they started with James Madison.

From President Monroe’s administration (1817-25) to the Carter administration (1977-81), the executive branch issued a total of 75 signing statements to protect presidential prerogatives. From Reagan’s administration through Clinton’s, the total number of signing statements ever issued, by all presidents, rose to a total 322.

In striking contrast to his predecessors, President Bush issued at least 435 signing statements in his first term alone.

According to “The Legal Significance of Presidential Signing Statements,” prepared by Assistant Attorney General Walter Dellinger, November 3, 1993 [PDF], since Madison U.S. presidents have used signing statements two different ways.

First, presidents use signing statements “to explain to the public, and more particularly to interested constituencies, what the President understands to be the likely effects of the bill, and how it coheres or fails to cohere with the Administration’s views or programs.”

As I understand this, the President might write “OK, I signed the fool bill, but when we go ahead with this thing it’s going to turn everybody’s ears bright green. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.”

Second, presidents use signing statements “to guide and direct Executive officials in interpreting or administering a statute.” I haven’t found a specific example of this circumstance, but if anyone else finds one please post it in the comments.

For many years presidential signing statements were only used as explained above. And in all those years I don’t believe anyone was much bothered by them. But along came the Reagan Administration, and the Reaganites came up with a new and more controversial twist, which was —

… the use of signing statements to announce the President’s view of the constitutionality of the legislation he is signing. This category embraces at least three species: statements that declare that the legislation (or relevant provisions) would be unconstitutional in certain applications; statements that purport to construe the legislation in a manner that would “save” it from unconstitutionality; and statements that state flatly that the legislation is unconstitutional on its face. Each of these species of statement may include a declaration as to how — or whether — the legislation will be enforced. … More boldly still, the President may declare in a signing statement that a provision of the bill before him is flatly unconstitutional, and that he will refuse to enforce it.

Now, there’s nothing in the Constitution that says a President can’t express an opinion that a law is unconstitutional. The notion that the Supreme Court is the only and final arbiter of constitutionality developed in the years after the Constitution was ratified. But until Reagan if a President believed a law was unconstitutional he vetoed it. And then the bill went back to Congress, which could decide to override the veto, or not, or revise the bill per the President’s request.

But now the President has made himself the final arbiter of constitutionality. Even if an overwhelming majority of Congress were to disagree with the President’s interpretation of the Constitution — too bad. And in the case of law that is meant to provide some congressional oversight of questionable presidential practices — too dangerous.

John Dean wrote for FindLaw (January 13, 2006):

Given the incredible number of constitutional challenges Bush is issuing to new laws, without vetoing them, his use of signing statements is going to sooner or later put him in an untenable position. And there is a strong argument that it has already put him in a position contrary to Supreme Court precedent, and the Constitution, vis-Ã -vis the veto power.

Bush is using signing statements like line item vetoes. Yet the Supreme Court has held the line item vetoes are unconstitutional. In 1988, in Clinton v. New York, the High Court said a president had to veto an entire law: Even Congress, with its Line Item Veto Act, could not permit him to veto provisions he might not like.

The Court held the Line Item Veto Act unconstitutional in that it violated the Constitution’s Presentment Clause. That Clause says that after a bill has passed both Houses, but “before it become[s] a Law,” it must be presented to the President, who “shall sign it” if he approves it, but “return it” – that is, veto the bill, in its entirety– if he does not.

Following the Court’s logic, and the spirit of the Presentment Clause, a president who finds part of a bill unconstitutional, ought to veto the entire bill — not sign it with reservations in a way that attempts to effectively veto part (and only part) of the bill. Yet that is exactly what Bush is doing. The Presentment Clause makes clear that the veto power is to be used with respect to a bill in its entirety, not in part.

As I recall, Junior wants line item veto power, too. I’m not sure how he plans to get around SCOTUS on that.

Above I cited a document written by Walter Dellinger, Assistant Attorney General, in 1993. Dellinger expressed the opinion that that use of signing statements to, in effect, veto part of a piece of legislation was constitutional. This was before SCOTUS ruled on line-item vetoes, and I think it can be argued that Junior has taken the signing statement thing way further than past presidents. But be prepared for the “Clinton did it too” arguments from the Right if Bush’s use of signing statements ever heats up into a big controversy on the Blogosphere.

More on signing statements, from an editorial in today’s Boston Globe:

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN’S warning that the Founding Fathers had created ”a republic, if you can keep it” came home this week with The Boston Globe’s report that President Bush had once again added a signing statement to a bill, undermining the intent of Congress. Bush said he would not be held to the USA Patriot Act’s requirement that the Justice Department keep closer track of the FBI’s new powers and report on their use to Congress. Weeks before, Bush used a signing statement to exempt himself from Senator John McCain’s antitorture amendment. …

… When Bush crossed his fingers behind his back on the antitorture bill, Senators McCain and John Warner, both Republicans, issued a statement saying Congress had specifically denied the president the waiver authority he claimed in the signing statement. They said the Armed Services Committee would monitor implementation of the law ”through strict oversight.” By the same token, Congress will have to insist on the reports required by the Patriot Act or watch as the principle of separation of powers turns into the practice of separation of the powerless.

Remember, back in Daddy’s day, Daddy would work with Republicans in Congress to establish an “alternative legislative history” of a bill that could be imposed by Daddy’s fiat after the bill was signed. But Junior ain’t workin’ with anybody in Congress. He’s just making up his own laws. This is one clue that Junior is going further with the signing statements than any president has gone before.

The Republicans and Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee submitted detailed questions to the Bush Administration regarding the NSA program, and the DoJ’s responses to both the Democrats’ questions and its responses to the Republicans’ are now available.

There are numerous noteworthy items, but the most significant, by far, is that the DoJ made clear to Congress that even if Congress passes some sort of newly amended FISA of the type which Sen. DeWine introduced, and even if the President “agrees” to it and signs it into law, the President still has the power to violate that law if he wants to. Put another way, the Administration is telling the Congress — again — that they can go and pass all the laws they want which purport to liberalize or restrict the President’s powers, and it does not matter, because the President has and intends to preserve the power to do whatever he wants regardless of what those laws provide.

The righties can make all the “Clinton did it too” arguments they can pile into a garbage truck. Junior’s out of control. He must be stopped.