Latin America holds some of the world’s most stringent abortion laws, yet it still has the developing world’s highest rate of abortions – a rate that is far higher even than in Western Europe, where abortion is widely and legally available. [Juan Forero, “Push to Loosen Abortion Laws in Latin America ,” The New York Times, December 3, 2005]

Usually left out of our endless abortion debates is the simple fact that making abortion illegal doesn’t stop it. Making abortion illegal only drives it underground, where it is unregulated.

Forero of the New York Times continues,

Regional health officials increasingly argue that tough laws have done little to slow abortions. The rate of abortions in Latin America is 37 per 1,000 women of childbearing age, the highest outside Eastern Europe, according to United Nations figures. Four million abortions, most of them illegal, take place in Latin America annually, the United Nations reports, and up to 5,000 women are believed to die each year from complications from abortions.

According to the Alan Guttmacher Institute,

Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland have abortion rates below 10 per 1,000 women of reproductive age; in all other countries of Western Europe and in the United States and Canada, rates are 10-23 per 1,000.

Romania, Cuba and Vietnam have the highest reported abortion rates in the world (78-83 abortions per 1,000 women). Rates are also above 50 per 1,000 in Chile and Peru.

Abortion is legal (with varying gestational limits) in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Romania, Cuba, and Vietnam. It is banned in Peru except to save the mother’s life. It is banned completely in Chile. Clearly, there is no correlation between abortion rates and abortion laws. (More on abortion laws worldwide here.)

The evidence suggests that legal status makes little difference to overall abortion levels. Levels are very high in Eastern Europe and low in Western Europe, yet abortion is broadly legal in both. And levels are far lower in Western Europe than in Latin America, where abortion is highly restricted (except in Cuba and Guyana). [“Sharing Responsibility: Women, Society & Abortion Worldwide” (Alan Guttmacher, 1999), p. 28 (PDF)]

If laws against abortion don’t stop abortion, why bother? The usual rebuttal to that question is that there is still murder and theft in spite of laws against murder and theft. My response is that (I suspect) such laws, and vigorous prosecutions thereof, slow murder and theft down a lot. That’s not something I can prove with comparative data, since I’m not aware of any place with no restrictions on homicide or theft, other than places so violent that no civil authority exists. But if you think about it, the building of communities–civilization itself–would be pretty much impossible with no safeguards against slaughter and pillage.

Yet Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, etc. are all civilized, last I heard.

I think laws banning abortion are comparable to one of America’s great failed social experiments, prohibition. Driving liquor underground didn’t exactly stop drinking, but it was great for organized crime.

A Guttmacher study of abortion in Latin America describes what happens underground:

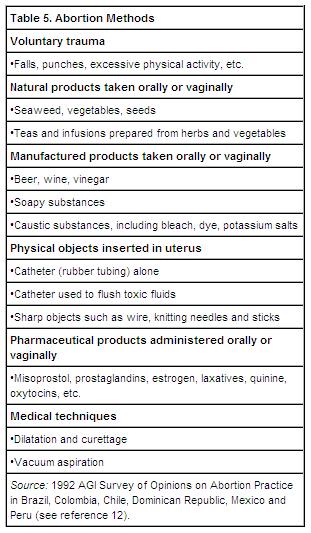

A 1993 study in Brazil, Colombia, Chile, the Dominican Republic, Mexico and Peru showed that women everywhere are familiar with teas and infusions made from herbs and other vegetable products that are believed to induce abortion (Table 5 [at the bottom of this post]).

If these products do not have the desired effect (and nobody knows whether they are genuine abortifacients), women are then likely to resort to riskier methods: the insertion of a rubber tube, caustic liquids or other foreign objects into the uterus; or the oral or vaginal application of powerful pharmaceutical and hormonal products. In Brazil, a pharmaceutical product usually prescribed for the treatment of gastric and duodenal ulcers, misoprostol (Cytotec), is widely used to terminate pregnancy.

In the six countries studied by Guttmacher (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and Peru), each year half a million women are hospitalized because of injuries received from crude, underground abortion.

Worldwide, Guttmacher says,

About one-third of women undergoing unsafe abortions experience serious complications, but fewer than half of these women receive hospital treatment.

Of the estimated 600,000 annual pregnancy-related deaths worldwide, about 13% (or 78,000) are related to complications of unsafe abortion.

Where abortion is legal and performed by medical professionals, however, “The risk of abortion complications is minimal; less than 1% of all abortion patients experience a major complication. … The risk of death associated with childbirth is about 11 times as high as that associated with abortion.”

Forero at the New York Times describes an incident in Pamplona, Colombia.

In this tradition-bound Roman Catholic town one day in April, two young women did what many here consider unthinkable: pregnant and scared, they took a cheap ulcer medication known to induce abortions. When the drug left them bleeding, they were treated at a local emergency room – then promptly arrested.

This incident helped galvanize a movement to loosen restrictions on abortion in Colombia and elsewhere in Latin America.

So far, no country has dropped its ban. But the effort, spurred by the high mortality rate among Latin American women who undergo clandestine abortions, has begun to loosen once ironclad restrictions and opened the door to more change.

And change is needed, because …

In an interview, a doctor in MedellÃn, Colombia, said that while he offered safe, if secret, abortions, many abortionists did not.

“In this profession, we see all kinds of things, like people using witchcraft, to whatever pills they can get their hands on,” said the doctor, who charges about $45 to carry out abortions in women’s homes. He spoke on condition that his name not be used, because performing an abortion in Colombia can lead to a prison term of more than four years.

“They open themselves up to incredible risks, from losing their reproductive systems or, through complications, their lives,” the doctor said.

Would American women be driven to take the same risks if legal abortions were entirely unavailable? If past is prologue, as this Guttmacher paper argues, the answer is yes.

First off, let’s put aside any notion that there were few abortions in America before Roe v. Wade. Since few abortions were officially reported as such before Roe it’s hard to know precisely how common abortion really was. However,

Estimates of the number of illegal abortions in the 1950s and 1960s ranged from 200,000 to 1.2 million per year. One analysis, extrapolating from data from North Carolina, concluded that an estimated 829,000 illegal or self-induced abortions occurred in 1967.

(By some coincidence, currently there are 1.2 million abortions performed per year in the U.S., and in a larger population than in the 1960s. It may be that the actual rate of abortions is somewhat lower now than it was pre-Roe.)

The pre-Roe estimates are based partly on the number of women admitted to hospitals because of complications from illegal abortion.

In 1962 alone, nearly 1,600 women were admitted to Harlem Hospital Center in New York City for incomplete abortions, which was one abortion-related hospital admission for every 42 deliveries at that hospital that year. In 1968, the University of Southern California Los Angeles County Medical Center, another large public facility serving primarily indigent patients, admitted 701 women with septic abortions, one admission for every 14 deliveries.

A clear racial disparity is evident in the data of mortality because of illegal abortion: In New York City in the early 1960s, one in four childbirth-related deaths among white women was due to abortion; in comparison, abortion accounted for one in two childbirth-related deaths among nonwhite and Puerto Rican women.

Even in the early 1970s, when abortion was legal in some states, a legal abortion was simply out of reach for many. Minority women suffered the most: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that in 1972 alone, 130,000 women obtained illegal or selfinduced procedures, 39 of whom died. Furthermore, from 1972 to 1974, the mortality rate due to illegal abortion for nonwhite women was 12 times that for white women.

Of course, if Roe v. Wade were overturned, abortion wouldn’t be illegal everywhere in the U.S. But if most of the South and Midwest banned abortions, as would probably be the case, women in those states would either go underground or travel to more progressive states to terminate pregnancies. And having to travel tends to delay the procedure, making it more dangerous.

(I have a vision of abortion clinics popping up around state borders, complete with their own motels for out-of-state guests. I can see the signs–Last chance for an abortion before you leave Massachusetts! Some of these place could be fairly posh, since poor women would resort to visiting the neighborhood basement abortionist. Or a coathanger.)

Which brings us to an editorial in today’s New York Times, “Judge Alito and Abortion.”

Judge Alito’s personal views are too well known to be debated – his mother recently told The Associated Press, “Of course, he’s against abortion.” Many people personally oppose abortions while supporting a woman’s right to reach her own decision. But when Judge Alito applied for a promotion to a legal position in the Reagan administration in 1985, he made it clear that he was not one of those people. He was “particularly proud,” he wrote, of his work as a lawyer on cases arguing “that the Constitution does not protect a right to an abortion.”

Judge Alito has tried to explain away that fairly unambiguous statement by saying he was simply an advocate seeking a job. That immediately raised questions about his credibility. Had he misrepresented his views to get a job? Is he misrepresenting them now since he is trying to get an even more important one?

In any case, a memo released later makes it clear that Judge Alito opposed Roe even when he wasn’t a job applicant. In 1985, he told his boss that two pending cases provided an “opportunity to advance the goals of overruling Roe v. Wade and, in the meantime, of mitigating its effects.” It is hard to believe that Judge Alito did not regard Roe as illegitimate when he wrote those words. If he agrees with Roe, it raises serious questions about what kind of lawyer he is, because in that case he would have been working to deny millions of women a fundamental right that he believed the Constitution guaranteed them.

Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Update: See also “A History of ‘Pro-Life’ Violence.”