If you need any more proof that the people steering the national Democratic party are a pack of inept, out-of-touch losers, just take a good look at the absurd Rube Goldberg nomination process we continue to be stuck with. In a recent column, Paul Waldman pointed out only some of the problems:

That’s not to mention the long list of appealing candidates who dropped out before anyone had a chance to vote for them, including Kamala Harris, Cory Booker and Julián Castro. I’m surely not the only one thinking that the race might be more compelling if they were still around.

A big part of the problem, Waldman continues, is that news media need somethng to report for several months before the voting starts. And, inadvertently, the way the pre-primary nomination race is reported in media distorts it quite a bit.

After a year or so of campaigning without any actual voting, we in the media are desperate for something concrete we can report on. And we want to write a story that changes, with a narrative momentum to it. That’s why we wind up getting influenced by how one or another candidate has performed relative to expectations, which when you think about it is utterly ludicrous.

Whose expectations are we talking about, after all? Those of journalists and pundits themselves. If someone exceeded expectations or fell short of expectations, it just means we inaccurately predicted how well they’d do in one state. And why should our mistaken assessment mean that in any objective way they did well or poorly?

It shouldn’t take a genius to understand that Joe Biden’s early lead in national polling had more to do with name recognition than anything else. Polls taken months before an election are not just unreliable; they are fantasies. People don’t form real opinions until they choose to focus on the race and pay attention, and for most that doesn’t happen until it’s close to time to vote. But in part because of an overwrought process in news media that jerked around our expectations, a lot of good people dropped out before anyone could vote for them.

The way the DNC decided who could be in the debates is another issue. I’m not sure what the answer is, but it seems weird that having a lot of money should qualify someone over years of government service.

Also: throughout these debates, with few exceptions, moderators’ questions were more about pushing candidates into controversy than illuminating their positions on issues. Many just repeated Republican talking points rather than ask honest questions that reflected they had a clue about the actual substance of issues. CNN was, IMO, far and away the worst of these, and the Dems should refuse to allow them to moderate debates in 2024. But between now and then serious thought needs to be given to how the debate format can best be designed to let the candidates present themselves to the American people. And then the hosts and moderators must agree to that format, or they don’t get the gig. Why this hasn’t been done already is, frankly, baffling.

And then there is the order of the primaries, which makes no sense. There has been no end of justifiable criticism of the outsize role played by Iowa and New Hampshire, for example. I think the old schedule needs to be entirely scrapped in favor of primaries that are grouped by regions, and Paul Waldman seems to have had a similar idea.

So what do we do about this? The longer-term answer is to change how we select nominees; a system of rotating regional primaries, in which all the voting would take place on four or five days, is one possibility.

My idea is to schedule primaries in groups of a few contiguous states, so that the candidates can focus on a region at a time. Instead of just Iowa, for example, candidates would focus on an upper midwest region that would include Illinois (arguably the most demographically representative state in the nation) and Wisconsin, Nebraska, maybe one or two more states. These states would have their primaries on the same day or at least within a week or so of each other.

This would reduce travel cost and media costs, since media markets often overlap state lines, as well as allow for a more representative demographic mix. Allow for some time in between each region so that candidates can spend some meaningful time there. As it is, candidates practically live in Iowa and New Hampshire for months while the rest of the nation gets only fleeting glimpses of them.

In 2017 I wrote a post about making the nomination process fairer. In that I was open to the idea of eliminating the caucuses, although not completely sold. Okay, now I’m sold. No more caucuses.

Another proposal was to allow anyone except registered Republicans to vote in Democratic primaries. That’s done in some states but not in other states. Allowing independents — whose votes we’ll need to win the general election — a say in choosing the nominee seems only sensible to me.

And, finally, just bleeping get rid of the superdelegates. This year the superdelegates won’t be allowed to vote on the first ballot, but they haven’t been eliminated altogether. I fear what mischief might be done at the convention if there is no clear winner.

But at least this year they aren’t reporting primary results with the superdelegate votes added in, the way they did in 2016. That was infuriating. In 2016 the vote gap between Clinton and Sanders was a lot closer than people realized, but because the vote totals that were reported always included the Clinton superdelegates, it looked as if Clinton was much further ahead in votes than she actually was.

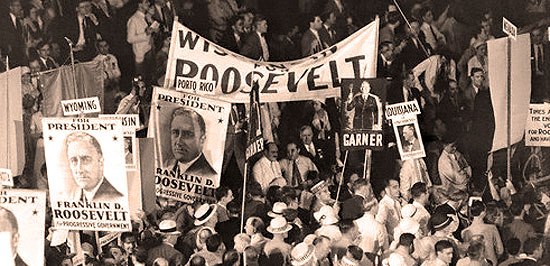

Franklin Roosevelt won the nomination on the fourth ballot in the 1932 Democratic National Convention.