I direct your attention to this video from the Re-elect Ed Markey to the Senate campaign.

This is a terrific video, and if I lived in Massachusetts I bet it would persuade me to vote for Markey. Well, that and the fact that Nancy Pelosi has endorsed his opponent, Joe Kennedy III. What happened to favoring incumbents, Nancy?

At the end, Markey says, “With all due respect, it’s time to start asking what your country can do for you.” Amen.

Annie Lowrey discusses The Lessons Americans Never Learn at The Atlantic. This is about the way Americans have been conditioned to not ask anything of their own government. It begins:

Across the country, parents are using Facebook to form “pandemic pods,” hiring tutors or out-of-work teachers to educate their kids as school district after school district announces that it will go partially or fully virtual. Beloved mom-and-pop stores are flooding sites such as GoFundMe to seek support from their sheltered-in-place patrons. Sick people are relying on COVID-19 relief funds and hospital-bill crowdfunding campaigns. And civic entrepreneurs are forming organizations that buy meals from down-on-their-luck restaurants and ferry them to exhausted essential workers.

These developments are a sign of American ingenuity. They are a measure of American community and can-do spirit, unleashed by social media and digital organizing. They are also a tragedy. The United States is forcing its citizens to bootstrap their way through a global catastrophe, saddling traumatized families with the burden of public administration and amplifying the country’s inequalities.

In functioning high-income countries, the government guarantees the provision of essential goods and services: medical care, transit between cities, supplies for public schools, financial support to weather a period of unemployment. But here, the government often fails to provide them. Need gives birth to invention, as well as deprivation.

John Kennedy’s famous line “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country” was delivered in 1961, a time when veterans of World War II pretty much ran the country. The Greatest Generation sacrificed a lot, but it also received a lot, both from the New Deal — which hadn’t been dismantled yet — and the GI bill. In the 1960s the American middle class still benefited from the Great Compression, a time in our economic history with the least economic inequality. Most economists will tell you the Great Compression ended in the 1970s. Real wages — meaning, wages adjusted for cost of living — for U.S. workers peaked in 1972 and have been stagnant or declining since. What wage gains there have been have mostly flowed to the top 10 percent of earners. And the gap between the very wealthy and the rest of us gets bigger and bigger.

And through the years we’ve all been conditioned to patch together our own safety nets. Even many of the “safety nets” that government hasn’t killed entirely are designed to not work and thereby frustrate and discourage people trying to use them; see, for example, unemployment compensation.

Back to Annie Lowrey

Long before 2020, many Americans were in the position of patching their own safety net and acting as their own city hall. They sought computers, crayons, and paper for elementary-school classrooms through online campaigns. They fell back on crowdfunding sites after a car accident, an appendectomy, a fight with cancer, a premature birth. They used ride-sharing when the bus never came.

Now the pandemic has shredded the country’s education infrastructure, decimated its network of child-care providers, eliminated millions of low-income jobs, forced the closure of hundreds of thousands of small businesses, and killed 170,000 people and counting. Thousands of people on the verge of eviction, thousands of businesses on the verge of bankruptcy, thousands of parents desperate for someone to watch their kids are turning to friends, family, and strangers on the internet for help.

Good ol’ American ingenuity.

America insists on repeating this lesson over and over and over again, never really learning it: No amount of private initiative or donor generosity can or will ever do what the government can. First, individuals, nonprofits, and companies simply don’t have the resources to provide public services at scale. A majority of GoFundMes do not reach their stated fundraising goal, with many never raising any money at all. Despite all those campaigns to save restaurants and bars, Yelp reported that 140,000 businesses listed on its service have closed since the pandemic recession started, many never to reopen; saving them would likely have required billions of dollars. Americans rack up nearly $90 billion in medical debt every year, more than twice the amount given to health-related charities.

Second, household income, charitable giving, business profits, and corporate investment all tend to be cyclical phenomena. When the economy collapses, they collapse. If the mill in a mill city shuts down, for instance, the city’s schools lose financing, its citizens lose their health insurance, its local nonprofits see a drop in donations, and its businesses see their turnover erode, all at once. Everybody has greater needs when everybody has less to give. Not so for the federal government, which runs a deficit in good times and a much bigger one in bad times. Its job is to flood individuals, businesses, and nonprofits with cash when an economic catastrophe hits. When it does not do that, other entities cannot bridge the macroeconomic gap.

How many times have we heard “conservatives” argue that government “welfare” programs should be scrapped and replaced by private charity? And how many column inches, how much bandwidth, has been given to patient explanations why that won’t work? Yet the argument never dies. This is by Mike Konczal, from 2014:

This vision has always been implicit in the conservative ascendancy. It existed in the 1980s, when President Reagan announced, “The size of the federal budget is not an appropriate barometer of social conscience or charitable concern,” and called for voluntarism to fill in the yawning gaps in the social safety net. It was made explicit in the 1990s, notably through Marvin Olasky’s The Tragedy of American Compassion, a treatise hailed by the likes of Newt Gingrich and William Bennett, which argued that a purely private nineteenth-century system of charitable and voluntary organizations did a better job providing for the common good than the twentieth-century welfare state. This idea is also the basis of Paul Ryan’s budget, which seeks to devolve and shrink the federal government at a rapid pace, lest the safety net turn “into a hammock that lulls able-bodied people into lives of dependency and complacency, that drains them of their will and their incentive to make the most of their lives.” It’s what Utah Senator Mike Lee references when he says that the “alternative to big government is not small government” but instead “a voluntary civil society.”

You might not remember this, but when Homeland Security and especially FEMA — staffed by amateur political appointees at the time — failed so miserably to respond to Hurricane Katrina, some of the Fox News bobbleheads were actually calling for entirely voluntary responses to natural disasters. I imagined being trapped under the unstable rubble of some collapsed building, surrounded by loose electrical wire, toxic chemicals, and rising water. Who do I want to rescue me? Professionals with special training and equipment? Or the Methodist Ladies Bible Study Circle?

The problem with emergency response is that one doesn’t need emergency responders all the time, so it’s all too tempting to balance that budget by cutting emergency preparedness, including pandemic preparedness, thinking that we can put something together when we need it. But that doesn’t work. We keep being taught how that doesn’t work, and we don’t learn. And do read Mike Konzcal’s piece for all the reasons private charity can’t replace government programs.

Back to Annie Lowrey:

Third, asking individuals to rely on themselves, their families, and their networks when trouble hits does not just reinforce existing disparities; it widens them, often along class, racial, and geographic lines. Consider how PTAs have become not just nice ways for parents to become involved in their children’s schools, but crass amplifiers of educational inequality. Parents in rich zip codes raise money for telescopes and enrichment classes, all the while refusing to redistribute desperately needed cash to schools in poorer zip codes.

And the kids in poorer zip codes need it more. Instead of addressing educational inequality we’ve cooked up charter schools, which often turn into money-sucking boondoggles, and voucher programs, ditto. These programs have been sold to us as ways to provide better education for all children, but we’ve been doing this for several years now, and there’s no clear evidence of that. In some places, voucher students have had worse testing scores than public school students. Not much bang for the buck, I’d say.

But this is part of the conservative belief that you can’t just give money to people. You can’t just invest money into improving public schools, because … . Um, no good reason. You just can’t. Instead, we come up with these Rube Goldberg programs that move funds all over the place (except directly into public schools) so that at least some of it can go into the pockets of a private education industry, and that will fix everything. But it doesn’t.

And for more on all the money wasted on right-wing “social” programs that don’t do anything but waste money, see my 2019 post, “Republican Moral Values.”

Annie Lowrey:

Finally, trying to replace the government with personal initiative requires an impossible amount of energy: raising money for your post-COVID-19 convalescence, working with multiple providers and a Kafkaesque health-payments infrastructure. Setting up a temporary school for your high-needs kid, interviewing teachers and working out payroll on your own. Figuring out how to get an Uber to an infrequent train to an unpredictable bus line to make it to your job. Liaising with dozens of nonprofits to save your restaurant. Searching for a day care, then arranging a nanny-share, then arguing for a reduced-price slot in a nursery school, because the United States has no public child-care and preschool system. It is exhausting.

“Exhausting” is pretty much life in America, even without covid-19. There are too many impediments and complications. Plans don’t work; safety nets collapse. Public transportation, where it exists at all, doesn’t go where you need it to go. You fall and break your leg, but the hospital across the street isn’t in your network, so you don’t dare seek treatment there. You miss work because your day care arrangements fall through. Maybe you lose pay; maybe you lose your job. Everything is always exhausting.

I still feel that I gave up too much of my adult life and spent away any hope of a retirement nest egg putting together day care arrangements for my kids so I could work. That was years ago; nothing has changed.

Taking on the obligation of public administration is a time suck and an attention suck, not just a money suck. And this necessity also, in its own way, amplifies the country’s existing disparities. People who are sick, poor, unemployed—these are the people we task with writing up a heartrending story and going hat-in-hand online. These are the people burdened with performing their trauma to garner support, bringing the public into their cancer journey, explaining what eviction and homelessness has meant, begging for someone to help so that they do not have to fire their staff and shut their doors.

The answer that virtually every other rich country has figured out: The government should act like a government, like its job is to provide these things. It should replace people’s income when a recession hits, and help businesses struggling through no fault of their own. It should guarantee simple, affordable access to medical care. It should provide child care and public education for families. And it should invest in trains and buses and classrooms. Fighting recessions and building public infrastructure, including care, health, and educational infrastructure—this should not be the work of citizens. When it is, let’s acknowledge that’s a tragedy.

I think of this tragedy as part of the legacy of Ronald Reagan, although it wasn’t just Reagan. In the years after World War II, the Greatest Generation was fine with getting subsidized mortgages and free college education. People on the whole had no big problem with government programs, as long as middle class white people were the prime beneficiaries. But there was a big shift in attitude during Lyndon Johnson’s administration, because programs he championed gave benefits to everybody. Some programs were even designed to help Black communities. And all of a sudden, all these Greatest Generation white people who were children during the Great Depression and owed their affluent lifestyles to the New Deal and GI Bill decided that government “welfare” programs were evil. Combine that with Cold War hysteria and Friedrich Hayek’s economic theories, and you’ve got a religion that says You people are on your own. Government exists for the military and corporations, not for you. And Reagan rose to glory as the high priest.

To see how deeply entrenched this thinking is, see I Spent 5 Years With Some of Trump’s Biggest Fans. Here’s What They Won’t Tell You. by Arlie Russell Hochschild in the September/October 2016 issue of Mother Jones. The subjects are working-class whites in Louisiana, many hanging on economically by their fingernails, who seemed to live with guilt and shame — the guilt of being short of money, the shame associated with “government handouts.” People are supposed to work and take care of themselves. That so many were failing was seen as personal failure, not a societal failure, and certainly not a failure of government. They fail to see that creating an economy that supports their ability to earn a decent living requires government involvement. If you leave everything to the private sector and “free markets,” all but the very wealthy are screwed.

Most other industrialized democracies have figured this out. We have not. And if we don’t figure it out pretty fast, the U.S. is likely to become the planet’s biggest third-world shit hole.

See also my recent post, Missouri and Medicaid, that pointed out how voters in the poorest counties, most of whom have no health insurance, and where hospitals are closing, voted against expanding Medicare. That’s the power of right-wing propaganda for you.

So yeah, the question of our times is, What should our country be doing for us? Promoting the general welfare is what a country, what a government, is for. There is no shame in that.

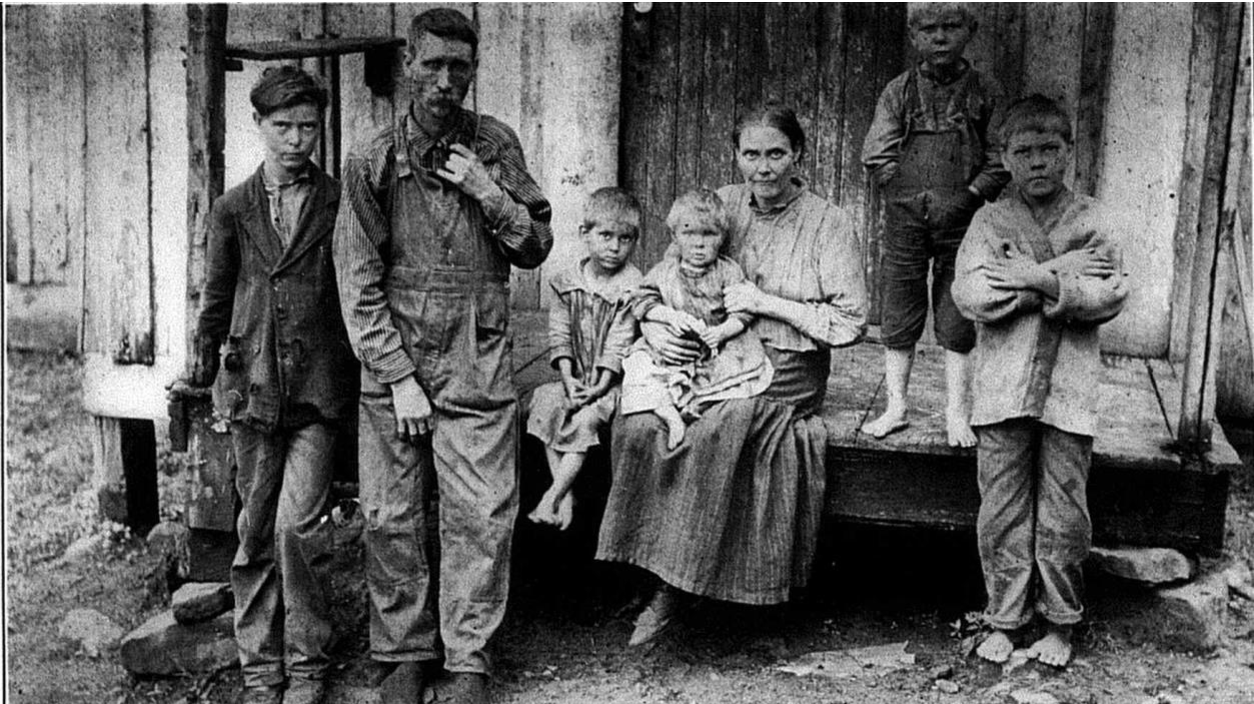

Is this our past or our future?