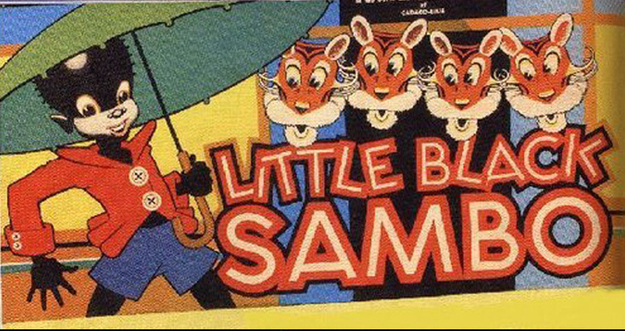

Illustration for Little Black Sambo board game, 1924.

I seriously hate the term “cancel culture” and think the whole controversy is bullshit. But now I’m seeing People Who Ought to Know Better wringing their hands over the “canceling” of six Dr. Seuss books and fretting that “canceling” is getting out of hand.

To which I say, get over it. This is not new. When I was a small child in the early1950s I remember being read Little Black Sambo (1899), still considered a kids’ lit classic at the time even though Langston Hughes had blasted it back in the 1930s as hurtful to Black children. In its day I believe Sambo was at least as widely read as The Cat in the Hat (which has not been “canceled,” I hope you know). It’s hard to find copies of Sambo now, although I understand the basic story (which is charming) has been retold in other children’s books in less blatantly racist ways.

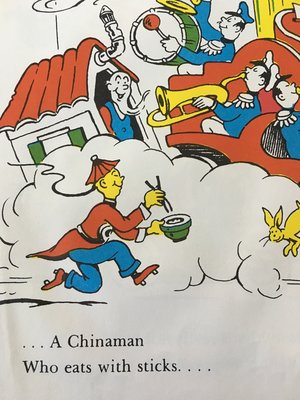

The six Dr. Seuss books dropped by the publisher, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, are And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, and The Cat’s Quizzer. Those last four I never heard of, and I have no memory of reading the first two, although I had heard of them. But I learned through googling that Mulberry (1937), at least, does have objectionable illustrations such as the one on the left. This is not something that would be published today.

The six Dr. Seuss books dropped by the publisher, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, are And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, and The Cat’s Quizzer. Those last four I never heard of, and I have no memory of reading the first two, although I had heard of them. But I learned through googling that Mulberry (1937), at least, does have objectionable illustrations such as the one on the left. This is not something that would be published today.

Mulberry is still available via Amazon, through resellers. A hardback copy is going for $749.99. If you have an old copy in the attic, you might want to find it now.

The argument was made that we shouldn’t judge the Seuss books based on today’s standards of what’s acceptable. That’s a lecture I make about historical figures and documents all the time. But I doubt that a parent reading the Mulberry Street book to a child is going to stop and explain why the illustration of the “Chinaman” isn’t acceptable, especially at a time when anti-Asian discrimination and violence are on the rise in this country.

Consider the old blackface minstrel shows. It’s one thing to learn about them as an artifact of history. It’s another entirely for someone to produce them today and bring them to a theater near you.

I want to call your attention to this story in the New York Post, which begins:

First it was Huck Finn. Then it was JK Rowling. Last week it was “The Muppet Show.” This week it’s Dumbo. It’s only a matter of time before “Star Wars” gets canceled and you know it.

Will Gen X please stand up? I have something I want to say to you — to us.

We grew up in a country that didn’t ban books. We all agreed that witch hunts and blacklists were bad. Censorship was an outrage. The 1980s were not that long ago. Don’t act like you don’t know what I’m talking about.

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn and The Muppet Show are as available as ever, as are JK Rowling’s Harry Potter books. (Rowling has been under fire because of comments about trans women.) Controversy and criticism are not censorship or “cancellation.” Dumbo got into trouble because of the crows, of course, and isn’t being shown or marketed by Disney any more.

There has always been controversy about art, you know. Did you know that Jonathan Swift (the author of Gulliver’s Travels) tried to stop the Dublin premiere of Handel’s Messiah oratorio in 1742? Many people thought it scandalous to present a musical work about Jesus in a music hall, to a paying audience.

Closer to home, remember all those years in which the Right tried to shut down the entire National Endowment of the Arts because of the infamous “Piss Christ” photo (1987)? Republicans did succeed in cutting the NEA budget, mostly riding on outrage about that photo. Somehow that doesn’t count as “cancelling.” Odd, that. But let’s go on.

In fact, all kinds of stuff was censored and revised and “canceled” before 1980. I take it the author of the New York Post article was only discussing the post-McCarthy period, say about 1960, until 1980, as the time when “witch hunts and blacklists were bad” (there was a lot of witch hunting and blacklisting in the 1950s) and “censorship was an outrage.” Books banned somewhere in the U.S. in the 1960s and 1970s included J.D. Salinger, Catcher in the Rye (naughty words); John Updike’s Rabbit, Run (explicit sex); Judy Blume, Forever (teenage sex); Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse Five (anti-Christian); and Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird (naughty words). Seriously, a lot of books were tossed from schools and libraries in the 1960s and 1970s, usually by conservatives.

Now, let’s go back to publishing and what I saw as a worker bee in the publishing industry, beginning in 1973 and my first job as a college graduate, working as a production editor for a university press.

In the 1970s, as the civil rights movement and second-wave feminism were having an impact, publishers realized that much of their backlist (older books still being reprinted and sold) contained a lot of racist and sexist crap that was suddenly embarassing. Those books were either revised for reprinting or quietly dropped from publishers’ catalogs. This was going on in academic and mass market publishing alike. And many children’s books, not just Sambo, were either retired or re-illustrated.

By the late 1970s I was working for a small publisher in Cincinnati, and we were going to produce a joke book for after-dinner speakers. The author was an older guy who had long made a living as a motivational speaker. One of his “jokes” was about wife beating. It’s a joke that might have been told by a stand-up comic on the old Ed Sullivan Show in the early 1960s. It probably was, actually. But in the 1970s, not so much. Attitudes were evolving.

I deleted the “joke” from the manuscript. The author was outraged. My manager, also a woman, backed me up. A lot of male managers might not have, yet. The stuff about his frigid wife and shrewish mother-and-law (mainstays of stand-up comedy once upon a time) stayed in, though.

I also remember being given the task of revising a backlist how-to book that was still selling well but was badly dated in many ways. It was full of such charming asides as “This is so simple even your wife could do it.” I rewrote a lot of that one. If the author complained I never heard; he may have been deceased.

“Serious” academic books also came under scrutiny. Before the 1970s one might often be reading a scholarly account of some ancient battle between, say, Persians and Greeks. And then you’d run into a sentence like “The Persians overran the Greeks and stole their women.” Somebody’s consciousness needed to be raised.

In the 1970s there were many studies and symposiums and what not examining conventions in language, with the aim of making our language more inclusive and respectful. It was during this period that, for example, mailman became mail carrier, chairman became just chair or chairperson, and retarded became developmentally disabled, This didn’t happen all at once; it was a long-drawn-out process taking place mostly in academia and publishing.

At some point, the people engaged in this process began to refer to is as “political correctness,” a phrase that had been coined in the 1930s to describe the way people in totalitarian states like the Soviet Union or Third Reich had to watch what they said. This was a kind of in-joke, originally. Then somebody published a humor book about political correctness that poked gentle fun at the process. This process did get a bit silly at times. I remember a manuscript for a middle school social studies text in which somebody wanted to change “Viking oarsmen” to “oarspersons,” for example.

The humor book became a best seller, and then everybody knew the phrase “political correctness.” PC became a pejorative in the 1980s and 1990s as conservative academics like Allan Bloom were fretting that the old Euro-centric curricula in literature and liberal arts generally were being challenged in favor of something more global. And then by the 1990s “PC” had become a rallying cry for bigots who resented having their speech corrected. I remember reading a social-psychology paper ca. 1998 that proposed White racists sincerely believe all other Whites are just as bigoted as they are but won’t admit it “because they’re just being PC.” “Political correctness” to right-wing extremists became a kind of censorship that didn’t allow people to speak “truth.”

And this brings us back to the Right’s phony outrage over Dr. Seuss books they’ve probably never read or cared about until they heard they were being “canceled.” Notice that news stories about the deicision by the publisher to drop six lesser-known and dated works from the backlist are nearly all illustrated by pictures of the beloved Cat in the Hat, who has not been affected in any way.

If these six books were not by such a famous author the publisher might have tweaked the text a bit and hired a new illustrator. That’s been done with some old children’s books; mostly readers don’t notice.

And it’s also the case that publishers drop books from their lists all the time and let them go out of print. If the publisher freely chooses to do this, it’s not censorship. It’s a business decision.

But let’s look at who is trying to “cancel” books because they don’t like the content. According to the American Library Association, the ten most challenged books of 2019 were mostly attacked because of their LGBTQ-inclusive content. Social conservatives were trying to get them out of schools and libraries, and probably succeeded in some places.

One of the two exceptions was The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood. The other exception was the Harry Potter series, but not because of JK Rowling’s comments about trans women. According to the ALA, the series has been removed from some schools and libraries “for referring to magic and witchcraft, for containing actual curses and spells, and for characters that use ‘nefarious means’ to attain goals.”

Damn, those spells really work? I’ll have to look some of them up again.