I want to add just a few more thoughts to yesterday’s post on the Republican tax cuts and why they are unpopular. Paul Krugman points out that the Bush tax cuts, which similarly gave a lot of money to the rich and cranked up the budget deficit, were popular. “Distributionally, the two tax cuts were broadly similar – as I said, big stuff for the rich, plus what amount to loss leaders for the middle class,” Krugman writes.

[The] answer might be that the Bush tax cut was pushed through in a very different fiscal environment. Readers of a certain age may recall that when Bush ran in 2000, the U.S. actually had a budget surplus – which he claimed simply to be giving back to voters. But during the Obama years voters were subjected to constant scare talk about deficits and debt – some from centrist scolds, some from the very Republicans who rammed through their tax cut. This may have made voters more aware of the downside to big tax cuts for the rich, even if they got a bit themselves.

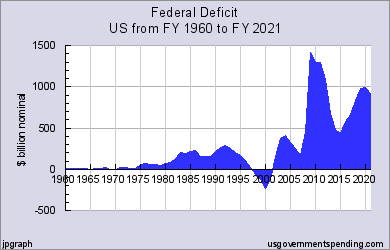

It’s really truly not 2001 any more. The economy had been, relatively speaking, pretty sweet in the late 1990s. It was the Age of Complacency. When George W. Bush talked about giving the budget surplus back to taxpayers, many people obviously assumed “budget surplus” meant there were piles of extra money in Washington somewhere that the government didn’t need, which of course isn’t how these things work. But remember back in the earlier 1990s when Ross Perot got everybody worked up about the deficit? Look at what has happened since:

Anyway, much has happened since George W. Bush became president, and I’m not just talking about terrorist attacks. A lot of people never really recovered from the financial meltdown in 2008. That episode also showed America that the big shots in Washington and on Wall Street can’t be trusted. The rising tide they created for themselves was made of the tears and sweat of working people, who didn’t benefit, but who paid the price when it all tumbled down. Meanwhile we’re in a country made of crumbling infrastructure, and with major cities deprived of safe drinking water, and with shrinking social programs, and too many people still doing without secure housing and decent health care, and there’s never enough money to fix that. But the rich get richer, and there’s always plenty of money for wars and parades and whatever ridiculous thing Scott Pruitt is doing.

Today, thanks to the tax cuts, big banks are reporting record profits. Few of us will benefit. And I think most people realize that, including even most Trump voters.

Martin Longman writes that pollsters have found people believe the tax breaks were just to reward Republican donors. Here he quotes the pollsters’ report:

One key difference the research found is voters are more receptive to the argument that Republicans are likelier to use government to personally enrich themselves and their wealthy donors. “They actually don’t think the tax plan was done for policy reasons,†Pollock said. “They don’t even think it was done for ideological reasons. They think it was done for purely dirty campaign reasons.â€

That’s because it was. Voters didn’t see that in 2001, but they understand it now. And maybe we’ve finally reached the point that Republicans cannot continue to skate on the illusory promise of prosperity through tax cuts. They’ve pulled that trick too many times; people see the scam.

But I’m not letting Democrats off the hook. Assuming the blue tide is real and the Dems take back the House and, maybe, the Senate this fall, the Dems can’t fall back into being the party of meaningless tweaks and Republican Lite. They have to be seen actually passing legislation that will benefit people, even if a Republican president vetoes it. And the problem with the Democrats is that a big chunk of the party is still complacent and still afraid that bold progressive initiatives will drive away the mythical center. Meanwhile, they take the votes of struggling minorities for granted, because hey — we’re not as bad as Republicans.

Thomas Edsall has an interesting column up —

Last week, in an essay for CityLab, Richard Florida, a professor of urban planning at the University of Toronto, described how housing costs are driving the growing division between upwardly and downwardly mobile populations within Democratic ranks:

The rise in housing inequality brings us face to face with a central paradox of today’s increasingly urbanized form of capitalism. The clustering of talent, industry, investment, and other economic assets in small parts of cities and metropolitan areas is at once the main engine of economic growth and the biggest driver of inequality. The ability to buy and own housing, much more than income or any other source of wealth, is a significant factor in the growing divides between the economy’s winners and losers.

Allies on Election Day, the two wings of the Democratic Party are growing further estranged in other aspects of their lives, driven apart by the movement of advantaged and disadvantaged populations within and between cities. These demographic patterns exacerbate intraparty tensions.

In brief: High-income urban professionals have plenty of money and are often oblivious to the hardships faced by others living in the same city. This is true of high-income urban professionals who call themselves “liberals” and are consistent Democratic voters.

Edsall links to this essay by Dani Rodrik, an economist at Harvard, who lays out the problem in stark terms. He addresses the rise of right-wing authoritarian faux populism in western democracies.

Why were democratic political systems not responsive early enough to the grievances that autocratic populists have successfully exploited – inequality and economic anxiety, decline of perceived social status, the chasm between elites and ordinary citizens? Had political parties, particularly of the center left, pursued a bolder agenda, perhaps the rise of right-wing, nativist political movements might have been averted.

And why didn’t the Left respond?

After the supply-side shocks of the 1970s dissolved the Keynesian consensus of the postwar era, and progressive taxation and the European welfare state had gone out of fashion, the vacuum was filled by market fundamentalism (also called neoliberalism) of the type championed by Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. The new wave also appeared to have caught the electorate’s imagination.

Instead of developing a credible alternative, politicians of the center left bought wholesale into the new disposition. Clinton’s New Democrats and Tony Blair’s New Labour acted as cheerleaders for globalization. The French socialists inexplicably became advocates of freeing up controls on international capital movements. Their only difference from the right was the sweeteners they promised in the form of more spending on social programs and education – which rarely became a reality.

The French economist Thomas Piketty has recently documented an interesting transformation in the social base of left-wing parties. Until the late 1960s, the poor generally voted for parties of the left, while the wealthy voted for the right. Since then, left-wing parties have been increasingly captured by the well-educated elite, whom Piketty calls the “Brahmin Left,†to distinguish them from the “Merchant†class whose members still vote for right-wing parties. Piketty argues that this bifurcation of the elite has insulated the political system from redistributive demands. The Brahmin Left is not friendly to redistribution, because it believes in meritocracy – a world in which effort gets rewarded and low incomes are more likely to be the result of insufficient effort than poor luck.

This is exactly what’s going on in the Democratic Party. In 2016 the Brahmin Left backed Hillary Clinton and could not for the life of them see why she was not a palatable candidate to most of the country, including working-class and young people of all races. The Brahmins are very proud of their support for civil rights for minorities, as they should be, but utterly oblivious to the way the system that benefits them is shafting everybody else. And this took us to the stupid post-2016 election squabbles about whether the Democratic Party should abandon civil rights in favor of economic issues, as if there was a reason the party couldn’t support both.

Trust in government has generally been declining in the US since the 1960s, with some ups and downs. There are similar trends in many European countries as well, especially in southern Europe. This suggests that progressive politicians who envisage an active government role in reshaping economic opportunities face an uphill battle in winning over the electorate. The fear of losing that battle may explain the timidity of the left’s response.

I’d say the real reason is that too many influential Democrats have their heads up their asses. My fear is that Democratic victories this December will translate into more Democratic complacency and inertia. People have seen through that scam, too. They are not willing to settle for crumbs any more. The party that really gets that will be in a great position to dominate American politics for a generation. The sad thing is, I don’t think either one really does.