As explained by a fellow named David Roth:

One of the defining aspects of the highly caffeinated conservative cable news sludge that Trump still chugs thirstily from morning until night is that it is hard to understand. It is intended to induce a state of heated clammy umbrage in the slack and softening minds of its consumers, and reliably does that, but it does this more through tone and frequency than by means of information. The point is to keep everyone watching both very upset and kind of curious about what exactly they’re upset about. …

… the idea is to repeat things enough that even passive viewers will be able to pick up the broad strokes, learn the heroes and villains and outrages and memes, get upset when they’re supposed to get upset and keep watching through the commercial breaks. Someone who watches enough hours of this will become not just familiar with but wholly conversant in all the salty phonemes that make up its language, but never quite know what the fuck they’re talking about.

Do read the whole thing; it’s a hoot. It’s also true. I’m sure we’ve all caught enough of right-wing media to know how true this is.

This is the Right’s superpower. Their followers believe what right-wing media and politicians say even though they don’t understand it, even though it makes no sense. And of course they don’t have to have facts to support their allegations. They can just make up whatever shit they want to make up, and it is believed. It is believed so strongly that you can show a true believer irrefutable evidence that what they believe isn’t true, and they won’t budge.

Last year righties were certain the coronavirus was a hoax; that entire U.S. cities were being burned to the ground by BLM and antifa, and that somehow massive voter fraud took the election from Donald Trump. Oh, and those thugs who attacked the Capitol Building? They were all freedom-loving patriots who were waved into the building by supportive police, and at the same time they were all antifa thugs just pretending to be Trump supporters to make Trump look bad.

We learned last week that Trump can scam the true believers out of their last dollars, and they’ll still support him. (For the latest on right-wing donation scamming, do see Tim Miller at The Bulwark.)

I still run into people who think we should be trying to engage in dialogue with the Right. Maybe once in a great while you might bump into an individual who is reachable. On the whole, though, when dealing with the true believers there’s no point. It would be less frustrating to try to explain algebra to a squirrel.

So now the Republican Party is engaged in a vast revision of election law so that they can suppress the votes of those who oppose them, because they realize that’s the only way they can win elections.

Stepping in to provide a philosophical argument for why suppressing votes is good — Kevin D. Williamson, a charmer who was once fired from The Atlantic for proposing that women who obtain abortions should be hanged. We don’t need more voters, he says, we need fewer but better voters. Note that he never clearly defines “better.”

There would be more voters if we made it easier to vote, and there would be more doctors if we didn’t require a license to practice medicine. The fact that we believe unqualified doctors to be a public menace but act as though unqualified voters were just stars in the splendid constellation of democracy indicates how little real esteem we actually have for the vote, in spite of our public pieties.

The 14th and 19th amendments make voting a right of all adult citizens, and the 26th Amendment set the minimum voting age at 18. Therefore, being 18 years old and a citizen are the only necessary qualifications . There is no constitutional right to a medical license.

And if we genuinely believe that the just powers of government are derived from the consent of the governed, we can’t very well argue that only a select group of “qualified” voters — “qualification” in this case being a vague and undefined thing unconnected to citizenship — should be permitted to give their consent. Narrowing the franchise is a clear path to oligarchy.

But of course Williamson doesn’t agree with the Declaration of Independence on this point. While he lacks the moral courage to come out and say so, one clearly infers that a “qualified” voter is one who thinks like Williamson and is presumed to possess mostly European DNA.

Williamson continues,

The real case — generally unstated — for encouraging more people to vote is a metaphysical one: that wider turnout in elections makes the government somehow more legitimate in a vague moral sense. But legitimacy is not popularity and popularity is not consent. The entire notion of representative government assumes that the actual business of governing requires fewer decision-makers rather than more.

The entire notion of representative government is that the people through elections choose who will represent them. And then the representatives make decisions about laws and policies on behalf of their constituents. It is presumed that in making laws and policies the representatives do what they think is right and do not need to canvass their constituents before every vote.

Williamson almost says this later in the essay —

Representatives are people who act in other people’s interests, which is distinct from carrying out a group’s stated demands as certified by majority vote.

Yes, but it’s the majority vote that gives representatives the legitimate authority to act in their constituents’ interests. Duh.

Voters — individually and in majorities — are as apt to be wrong about things as right about them, often vote from low motives such as bigotry and spite, and very often are contentedly ignorant. That is one of the reasons why the original constitutional architecture of this country gave voters a narrowly limited say in most things and took some things — freedom of speech, freedom of religion, etc. — off the voters’ table entirely.

Yes, voters can be wrong; we see that in every election when some of the same corrupt old windbags get reelected. But other than the prohibitions on the federal government written into the Bill of Rights, I can’t think of any way that the “original constitutional architecture” limited the federal government from responding to the will of the voters in any matter. It’s true that over the years ideas about the proper role of the federal government in many matters has changed, but that doesn’t have anything to do with “constitutional architecture” that I can see.

It is easy to think of critical moments in American history when giving the majority its way would have produced horrifying results. If we’d had a fair and open national plebiscite about slavery on December 6, 1865, slavery would have won in a landslide.

[History lecture begins] No, slavery would not have won in a landslide in 1865.

There actually was something close to a national “fair and open plebiscite about slavery” held on November 6, 1860. This was the presidential election. The most prominent plank in Abraham Lincoln’s platform was a promise to keep slavery from spreading out of the slave states and into the western territories. Lincoln won easily against three other candidates.

The Democratic party split in half over slavery and nominated two candidates. The unabashedly pro-slavery-in-the-territories Democratic candidate was John Breckinridge, who won most of the slave states. He came in third in the popular vote although second in the electoral college. Stephen Douglas, who called for new states to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery, was the other Democratic candidate, and he was second in the popular vote and third in the EC.

The fourth candidate, John Bell, was anti-secession but did not take a postion on slavery. Bell won Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia.

Note that at the time no candidate, not even Lincoln, called for abolishing slavery in the existing slave states. Lincoln may have wished to do so, but he believed such a thing required a constitutional amendment that was not bloody likely to happen at the time. Voters in “free soil” states were mostly ambivalent about slavery down South but believed passionately that it should be confined to the South and not allowed to spread. They were also concerned that the Dred Scott decision opened the door to allowing slave owners to move into “free soil” states and keep their “property” enslaved. Basically, we’re looking at NIMBY — a majority of voters in non-slave states were willing to tolerate slavery in the slave states, but they didn’t want it in their back yards. Or the territories.

But if voters were ambivalent about slavery in 1860, by 1865 a considerable majority hated the slave-owning Southern plantation class with with a white-hot passion, and there is no way a majority would have voted to let them waltz back to their plantations to keep people enslaved as if nothing had happened. So the 13th Amdnement abolishing slavery was ratified on December 6, 1865, and I’ve seen nothing to suggest a majority of voters opposed this. [History lecture ends.]

Back to Williamson:

Representatives are people who act in other people’s interests, which is distinct from carrying out a group’s stated demands as certified by majority vote. Legitimacy involves, among other interests, the government’s responsibility to people who are not voters, such as children, mentally incapacitated people, incarcerated felons, and non-citizen permanent residents. Their interests matter, too, but we do not extend the vote to them. So we require a more sophisticated conception of legitimacy than one-man, one-vote, majority rule. To vote is only to register one’s individual, personal preference, but democratic citizenship imposes broader duties and obligations. When we fail to meet that broader responsibility, the result is dysfunction: It is no accident that we are heaping debt upon our children, who cannot vote, in order to pay for benefits dear to the most active and reliable voters. That’s what you get from having lots of voting but relatively little responsible citizenship.

It’s kind of rich that a conservative would express such tender concerns for the welfare of children, incarcerated people, and non-citizen permanent residents. However, one assumes that most adult voters care about children and have opinions about policies that affect them. (Note that we also have a large faction of voters who are more concerned about fetuses than children, and vote accordingly, often at the expense of their own economic well-being.) What Williamson portrays as a disregard for children is really a disagreement about what policies are better for the nation, including the children. It may be that fewer of us think about the special concerns of the incarcerated and resident foreign nationals, unless those concerns are called to our attention, but it simply isn’t true that most voters are unconcerned about the well being of others. We are not a nation of sociopaths, I don’t think.

As far as mental disabilities are concerned, it’s not clear that such people are legally and constitutionally blocked from voting. I looked it up. A few states still enforce old laws on the books that take the franchise away from people declared “mentally incompetent,” but in most of the U.S. if you are functional enough to register to vote and can show up at the correct polling place on election day and use a voting machine, you can vote. If you are too demented to do those things, then you won’t be voting, will you?

I skipped over much of the first half of the essay, where Williamson wallows in the straw-man argument that Democrats oppose Republican demands for more stringent ID requirements for voting because they are unconcerned about voter fraud.

No, dear Mr. Moron Williamson, that is not the case. If there were evidence that in-person voter fraud happened at a high enough rate to change election results we would certainly want to address it. But there isn’t. Study after study has found that incidents of people using a false identity to vote are extremely rare. Obvously, the safeguards already in place to discourage in-person voter fraud are working just fine. Placing ever more burdensome requirements on people before they can vote is a solution without a problem. It’s also a handy voter suppression tool, especially against voters with less time and fewer resources to go chasing down this or that particular document.

And so on. The whole essay is one howler after another. But, you know, if you’re a rightie you don’t have to make sense. Any assemblage of words, no matter how inaccurate or illogical, will do for an argument.

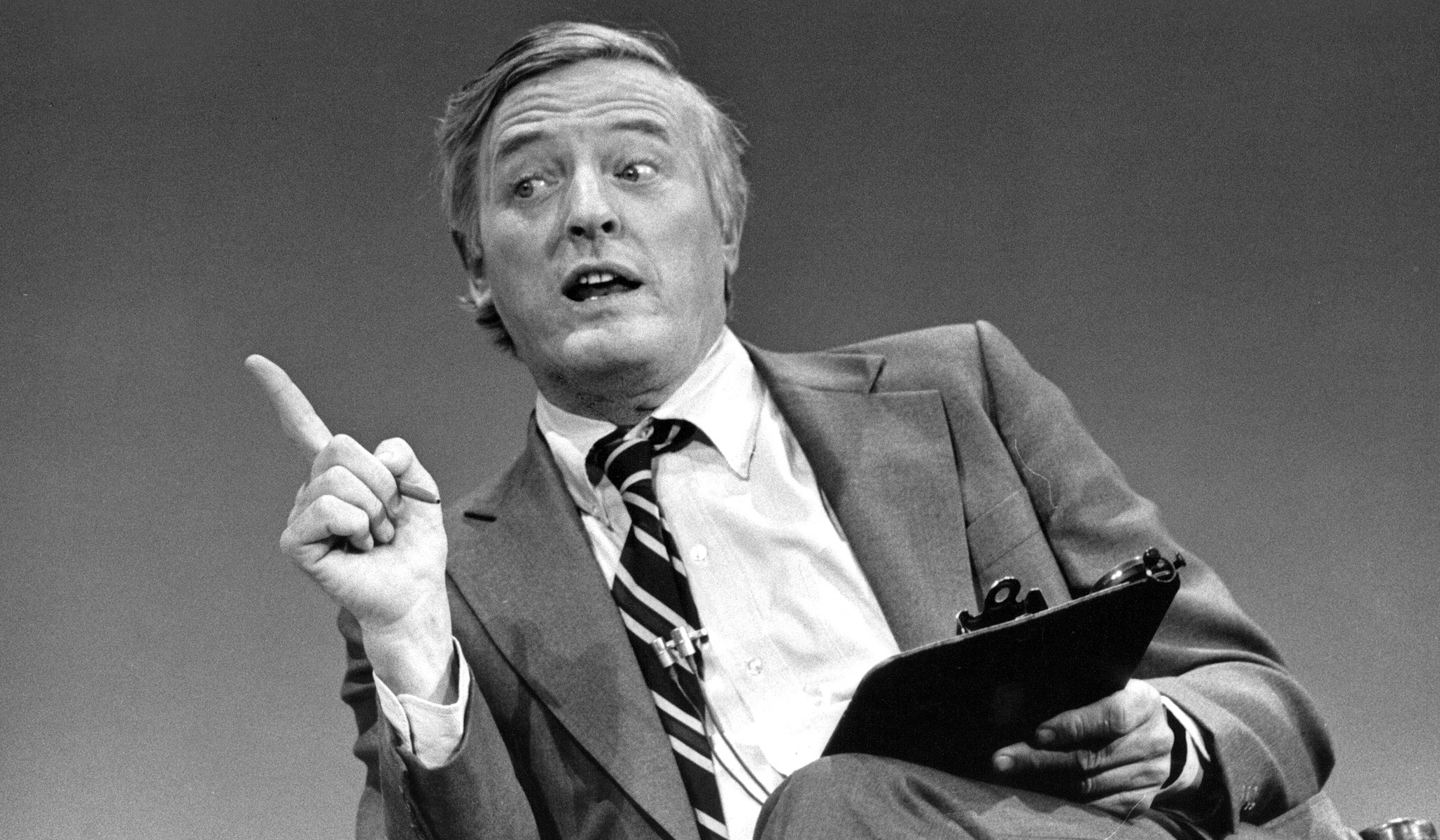

One might sorrow over the sorry state of today’s American conservative (and National Review essayist), once represented by brainy elites like William Buckley and now by barely cognitive bigots like Kevin Williamson. But at WaPo, Philip Bump — who also takes issue with Williamson’s essay — reminds us that maybe things haven’t changed that much. He quotes Buckley from 1957 —

“It is not easy, and it is unpleasant, to adduce statistics evidencing the median cultural superiority of White over Negro: but it is a fact that obtrudes, one that cannot be hidden by ever-so-busy egalitarians and anthropologists. The question, as far as the White community is concerned, is whether the claims of civilization supersede those of universal suffrage. The British believe they do, and acted accordingly, in Kenya, where the choice was dramatically one between civilization and barbarism, and elsewhere; the South, where the conflict is by no means dramatic, as in Kenya, nevertheless perceives important qualitative differences between its culture and the Negroes’, and intends to assert its own. NATIONAL REVIEW believes that the South’s premises are correct.”

So perhaps thngs haven’t changed that much. The only difference is that Williamson uses fewer semicolons and is more constrained than Buckley was from just coming out and saying what he means by “better.”

William F. Buckley